Halloween

‘The rowdiest Hallowe’en’: What happened when Toronto teenagers rioted in 1945When youth decided to cut the high-school dance, the result was a spontaneous street party — complete with broken windows, barricades, and flaming streetcar tracks

https://www.tvo.org/article/the-rowdiest-halloween-what-happened-when-toronto-teenagers-rioted-in-1945

Written by Daniel Panneton Oct 31, 2022

https://www.tvo.org/article/the-rowdiest-halloween-what-happened-when-toronto-teenagers-rioted-in-1945

Written by Daniel Panneton Oct 31, 2022

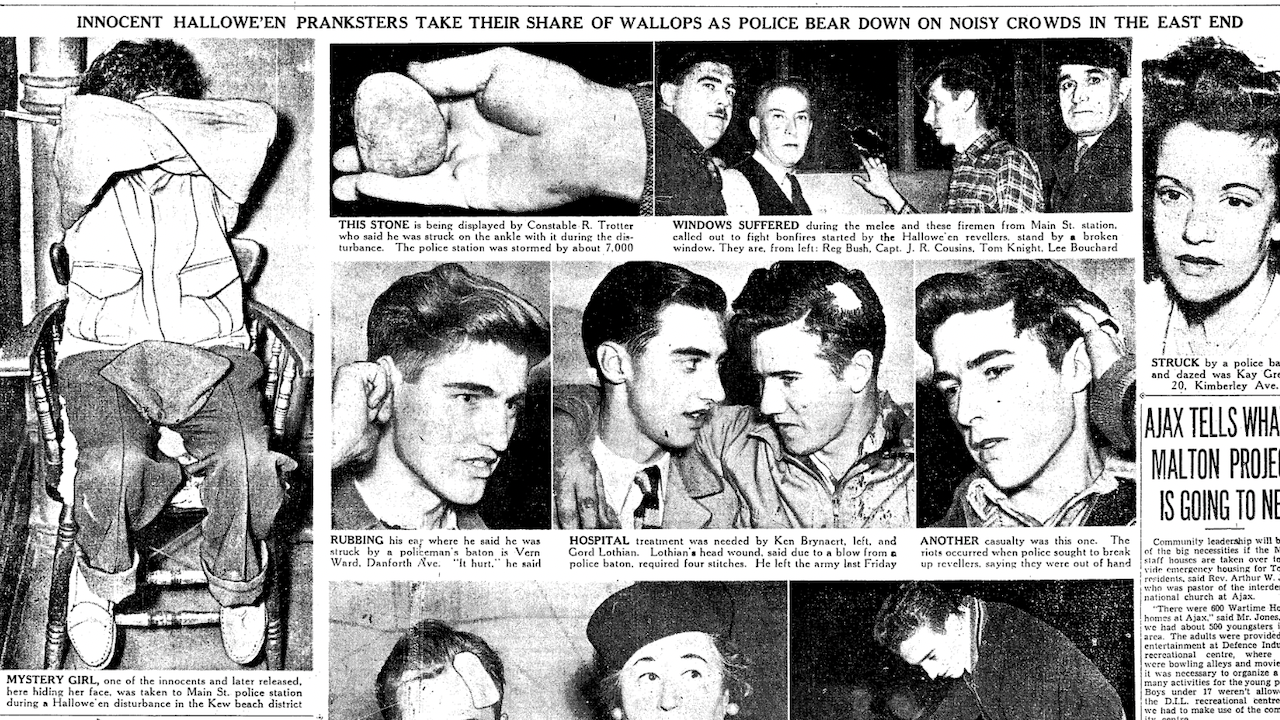

Detail from the front page of the November 1, 1945 edition of the Toronto Star. (ProQuest Historical Newspapers)

Torontonians had no reason to assume that there would be particular trouble on Halloween 1945. Sure, there was local history of pranksters throwing firecrackers into mailboxes and opening fire hydrants, but it was nothing the police couldn’t handle, and besides — who hadn’t been young once?

By the time the sun rose on All Saints’ Day, 13 teenaged Torontonians were in jail, and dozens of police officers, rioters, and bystanders were nursing minor injuries. Around the city, window fragments and smoking debris littered commercial streets, erupting fire hydrants had to be closed, and streetcar equipment had to be repaired. It was, in the words of a Globe & Mail reporter, “the rowdiest Hallowe’en in the city’s history.”

It began when groups of local teenagers blew off the Halloween dance at a local school, preferring to gather instead in a loosely organized illicit street party near the intersection of Queen Street and Wineva Avenue around 8 or 9 pm. Before long, the area was teeming with thousands; the revelry quickly descended into wanton destruction. Members of the crowd tore down a fence at Hammersmith Avenue and then used it to build a massive bonfire in the middle of Queen. The teens also built small barricades with stolen blocks of cement and debris from a nearby excavation, where they also found the scantlings and planks needed to keep their fire alight. As the party escalated, someone showed up with a can of gasoline. It was poured all over the streetcar tracks, which were promptly (true to the evening’s theme) set on fire. Police would later claim that the streetcar-track fires had stretched for blocks along Queen.

A TTC investigator testified that the streetcars had been in use when the tracks were set on fire, and described the risk posed to his passengers: “Flames which rose all of four feet from fires on the rails were started by the youths. The cars could ride through the flames, but if forced to an emergency stop the cars would burn.” When asked about the passengers, the investigator replied, “The people would certainly burn too.”

Police on the scene had difficulty controlling the crowd, and officers from other divisions had to be rushed to the scene. When it became clear that the “shooting flames” threatened local buildings, a call went out for all available constables and firefighters in the city to help disperse the crowd. Mounted police riding on the sidewalks to try to disperse the crowd were pelted with rocks and almost pulled off their horses. The police arrested 13 rioters, including suspected ringleader Thomas Padgett. All arrestees were then shuttled in vehicles to the Main Street Police Station down the road.

The crowd, which had been growing in size and intensity and filled Queen from Beach Avenue to Lee Avenue, erupted. Rioters opened fire hydrants, successfully hitting around 35 in the Beaches area. Newspapers reported that, under the influence of other ringleaders, 7,000 teenagers “ran the half mile” to the station while chanting for Padgett’s release. The police hastily formed a line around the station. Upon reaching their destination, the rioters resumed insulting the officers and started to hurl massive rocks through station windows. A small group almost broke through the police line, and the crowd attempted to storm the station to liberate their comrades, but all were beaten back. Half an hour later, the fire department arrived and turned two hoses on the crowd, scattering the rioters in 10 minutes, but not before enduring a barrage of bricks, sticks, and stones. After the crowd had dispersed, a few retreated south and regrouped at Kingston Road and Bingham Avenue. Their rampage resumed briefly when they smashed a few streetlights, but the arrival of more police put a damper on the rally.

Three individuals singled out as alleged ringleaders were granted a $1,000 bail, which they could not meet. Originally set at $200, the Crown attorney raised it after consultation with the magistrate responsible for bringing them in. Eventually, the ringleaders received $100 fines, while other arrestees were fined $25.

The Beaches wasn’t the only neighbourhood to witness children running amok that night. There were TTC obstructions around the east end, notably at Broadview Avenue and Danforth Road. In a disturbing reminder that antisemitism had not ended with the Second World War, the word “Jew” was written on businesses in the west end thought to be Jewish-owned. Another group of hoodlums smashed windows along College Street before fleeing north on Dovercourt Road, where they were captured by a TTC conductor who held them until the police arrived. Each boy was ordered to pay $18 to repair the damage. At Queen’s Park Circle, a group of youths beat up three University of Toronto students who were trying to put out the fires. A house porch in North York was set on fire, and a number of additional fire hydrants were opened and a CN railway track obstructed in Weston.

There were also minor outbreaks of Halloween-related violence around the country. In Ottawa, someone threw a teargas bomb into the stairway leading to a bowling alley, causing a panicked evacuation. In Prince Rupert, 200 high-school students stormed the city police station to demand the release of two arrested boys. Vancouver saw a tussle between police and a gang of youth who were parading through streets and blocking streetcar tracks; in Hamilton, 16 youth attacked and injured two returning soldiers who were waiting for a streetcar

While the police claimed they hadn’t resorted to violence to break up the riot, that wasn’t exactly true. The Star reported that “billies were flourished and a large number of youths showed bruises on their heads and legs when the disturbance ended.” Padgett claimed that he was an innocent bystander who’d been randomly clubbed, and another arrestee claimed that he’d intervened only after seeing an officer beat a rioter with a blackjack. Another witness testified that he’d seen officers wielding their flashlights as weapons.

The Halloween violence shocked Ontarians and received extensive syndicated press coverage. While previous years had seen isolated reports of rowdiness and vandalism, several thousand teens trying to maybe barbeque transit users in 1945 crossed the line, and local anxieties about juvenile delinquency and street gangs deepened.

For contemporary observers, the explanation was clear: the youth didn’t have enough healthy outlets or activities available to them (a conclusion that ignores the fact that the rioters did have a another option that night — the school dance). In Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night, historian Nicholas Rogers details how the local press called for attempts to defang and render the night “child-like.” Practices such as trick-or-treating gained popularity around this period, partially as a means of defusing more destructive elements.

Although Halloween had been a rowdy declaration of youth-in-transition and transgression for decades, events like the 1945 Halloween riot in Toronto fuelled a form of respectability politics that demanded the evening become more palatable.

Torontonians had no reason to assume that there would be particular trouble on Halloween 1945. Sure, there was local history of pranksters throwing firecrackers into mailboxes and opening fire hydrants, but it was nothing the police couldn’t handle, and besides — who hadn’t been young once?

By the time the sun rose on All Saints’ Day, 13 teenaged Torontonians were in jail, and dozens of police officers, rioters, and bystanders were nursing minor injuries. Around the city, window fragments and smoking debris littered commercial streets, erupting fire hydrants had to be closed, and streetcar equipment had to be repaired. It was, in the words of a Globe & Mail reporter, “the rowdiest Hallowe’en in the city’s history.”

It began when groups of local teenagers blew off the Halloween dance at a local school, preferring to gather instead in a loosely organized illicit street party near the intersection of Queen Street and Wineva Avenue around 8 or 9 pm. Before long, the area was teeming with thousands; the revelry quickly descended into wanton destruction. Members of the crowd tore down a fence at Hammersmith Avenue and then used it to build a massive bonfire in the middle of Queen. The teens also built small barricades with stolen blocks of cement and debris from a nearby excavation, where they also found the scantlings and planks needed to keep their fire alight. As the party escalated, someone showed up with a can of gasoline. It was poured all over the streetcar tracks, which were promptly (true to the evening’s theme) set on fire. Police would later claim that the streetcar-track fires had stretched for blocks along Queen.

A TTC investigator testified that the streetcars had been in use when the tracks were set on fire, and described the risk posed to his passengers: “Flames which rose all of four feet from fires on the rails were started by the youths. The cars could ride through the flames, but if forced to an emergency stop the cars would burn.” When asked about the passengers, the investigator replied, “The people would certainly burn too.”

Police on the scene had difficulty controlling the crowd, and officers from other divisions had to be rushed to the scene. When it became clear that the “shooting flames” threatened local buildings, a call went out for all available constables and firefighters in the city to help disperse the crowd. Mounted police riding on the sidewalks to try to disperse the crowd were pelted with rocks and almost pulled off their horses. The police arrested 13 rioters, including suspected ringleader Thomas Padgett. All arrestees were then shuttled in vehicles to the Main Street Police Station down the road.

The crowd, which had been growing in size and intensity and filled Queen from Beach Avenue to Lee Avenue, erupted. Rioters opened fire hydrants, successfully hitting around 35 in the Beaches area. Newspapers reported that, under the influence of other ringleaders, 7,000 teenagers “ran the half mile” to the station while chanting for Padgett’s release. The police hastily formed a line around the station. Upon reaching their destination, the rioters resumed insulting the officers and started to hurl massive rocks through station windows. A small group almost broke through the police line, and the crowd attempted to storm the station to liberate their comrades, but all were beaten back. Half an hour later, the fire department arrived and turned two hoses on the crowd, scattering the rioters in 10 minutes, but not before enduring a barrage of bricks, sticks, and stones. After the crowd had dispersed, a few retreated south and regrouped at Kingston Road and Bingham Avenue. Their rampage resumed briefly when they smashed a few streetlights, but the arrival of more police put a damper on the rally.

Three individuals singled out as alleged ringleaders were granted a $1,000 bail, which they could not meet. Originally set at $200, the Crown attorney raised it after consultation with the magistrate responsible for bringing them in. Eventually, the ringleaders received $100 fines, while other arrestees were fined $25.

The Beaches wasn’t the only neighbourhood to witness children running amok that night. There were TTC obstructions around the east end, notably at Broadview Avenue and Danforth Road. In a disturbing reminder that antisemitism had not ended with the Second World War, the word “Jew” was written on businesses in the west end thought to be Jewish-owned. Another group of hoodlums smashed windows along College Street before fleeing north on Dovercourt Road, where they were captured by a TTC conductor who held them until the police arrived. Each boy was ordered to pay $18 to repair the damage. At Queen’s Park Circle, a group of youths beat up three University of Toronto students who were trying to put out the fires. A house porch in North York was set on fire, and a number of additional fire hydrants were opened and a CN railway track obstructed in Weston.

There were also minor outbreaks of Halloween-related violence around the country. In Ottawa, someone threw a teargas bomb into the stairway leading to a bowling alley, causing a panicked evacuation. In Prince Rupert, 200 high-school students stormed the city police station to demand the release of two arrested boys. Vancouver saw a tussle between police and a gang of youth who were parading through streets and blocking streetcar tracks; in Hamilton, 16 youth attacked and injured two returning soldiers who were waiting for a streetcar

While the police claimed they hadn’t resorted to violence to break up the riot, that wasn’t exactly true. The Star reported that “billies were flourished and a large number of youths showed bruises on their heads and legs when the disturbance ended.” Padgett claimed that he was an innocent bystander who’d been randomly clubbed, and another arrestee claimed that he’d intervened only after seeing an officer beat a rioter with a blackjack. Another witness testified that he’d seen officers wielding their flashlights as weapons.

The Halloween violence shocked Ontarians and received extensive syndicated press coverage. While previous years had seen isolated reports of rowdiness and vandalism, several thousand teens trying to maybe barbeque transit users in 1945 crossed the line, and local anxieties about juvenile delinquency and street gangs deepened.

For contemporary observers, the explanation was clear: the youth didn’t have enough healthy outlets or activities available to them (a conclusion that ignores the fact that the rioters did have a another option that night — the school dance). In Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night, historian Nicholas Rogers details how the local press called for attempts to defang and render the night “child-like.” Practices such as trick-or-treating gained popularity around this period, partially as a means of defusing more destructive elements.

Although Halloween had been a rowdy declaration of youth-in-transition and transgression for decades, events like the 1945 Halloween riot in Toronto fuelled a form of respectability politics that demanded the evening become more palatable.