EAST YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY

EXECUTIVE BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Mission

East York Historical Society was formed in 1980 and incorporated in 1981 as a non-profit corporation affiliated with Ontario Historical Society to bring together people interested in the diverse heritage of

East York, to research, retain, preserve and present historical data pertaining to the region.

East York Historical Society financial support is provided by Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport (Speakers).

East York, to research, retain, preserve and present historical data pertaining to the region.

East York Historical Society financial support is provided by Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport (Speakers).

ALL ARE WELCOME TO OUR EVENING GENERAL MEETINGS

FREE ADMISSION

Meetings are held on the last Tuesday of January, March, May, September and AGM November at the S. Walter Stewart Library @ 170 Memorial Park Ave (northwest corner of Memorial Park and Durant Avenues) at 7:00 pm and include an illustrated presentation on a subject.

East York Historical Society meetings are co-sponsored by both the Toronto Public Library (S. Walter Stewart Branch) and East York Historical Society.

East York Historical Society meetings are co-sponsored by both the Toronto Public Library (S. Walter Stewart Branch) and East York Historical Society.

LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We acknowledge that the lands S. Walter Stewart Library stands on today, which are the same lands we inhabit, is the traditional territory of many nations, including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg (“Ah-nish-na-be”), the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee (“How-den-no-show-nee”) and the Wendat peoples and is now home to many diverse First Nations, Inuit and Metis peoples.

We also acknowledge that Toronto is covered by Treaty 13, signed with the Mississaugas of the Credit, and the Williams Treaty, signed with multiple Mississaugas and Chippewa bands.

https://ofl.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017.05.31-Traditional-Territory-Acknowledgement-in-Ont.pdf

We also acknowledge that Toronto is covered by Treaty 13, signed with the Mississaugas of the Credit, and the Williams Treaty, signed with multiple Mississaugas and Chippewa bands.

https://ofl.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017.05.31-Traditional-Territory-Acknowledgement-in-Ont.pdf

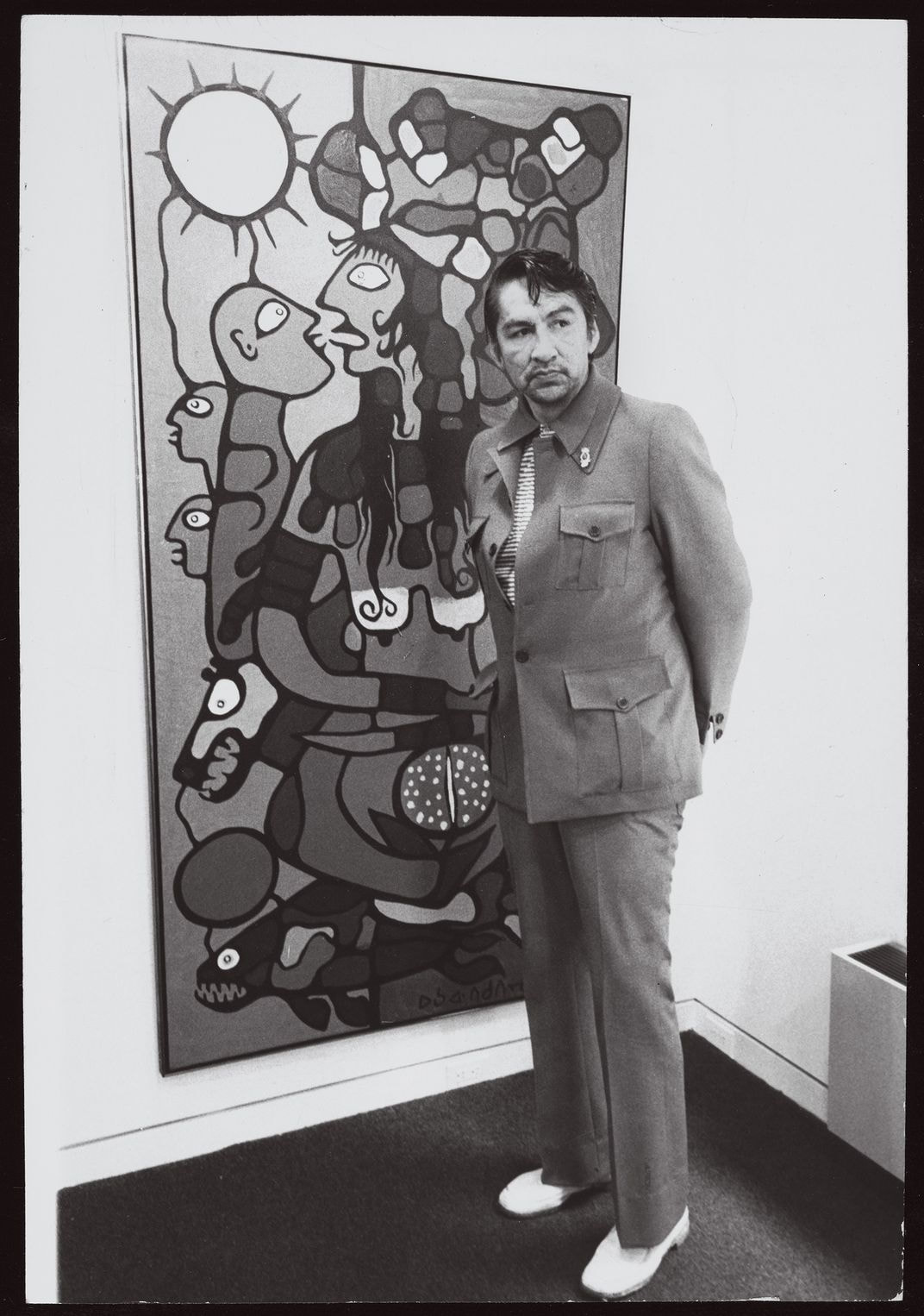

NORVAL MORRISSEAU

ARTWORK of RENOWNED ANISHNAABE ARTIST

(b. March 14, 1932 - December 4, 2007 (age 75 years), Toronto

Norval Morrisseau CM RCA, also known as Copper Thunderbird, was an Indigenous Canadian artist from the Bingwi Neyaashi Anishinaabek First Nation. He is widely regarded as the grandfather of contemporary Indigenous art in Canada. Wikipedia

ARTWORK of RENOWNED ANISHNAABE ARTIST

(b. March 14, 1932 - December 4, 2007 (age 75 years), Toronto

Norval Morrisseau CM RCA, also known as Copper Thunderbird, was an Indigenous Canadian artist from the Bingwi Neyaashi Anishinaabek First Nation. He is widely regarded as the grandfather of contemporary Indigenous art in Canada. Wikipedia

The great painter Norval Morrisseau and East York Historical Society President Pat Barnett on 17th September, 1997 at his Art Exhibition at Kinsman Robinson Gallery in Yorkville, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

This was a very special day for me to meet Mr. Norval Morrisseau.

This was a very special day for me to meet Mr. Norval Morrisseau.

Inside the Biggest Art Fraud in History

|

Inside the Biggest Art Fraud in HistoryA decades-long forgery scheme ensnared Canada’s most famous Indigenous artist, a rock musician turned sleuth and several top museums. Here’s how investigators unraveled the incredible scam

By Michael Jordan Smith It wasn’t until this past year, more than 15 years after the artist died from complications related to Parkinson’s, that an unlikely consortium of investigators, led by a homicide cop from the small city of Thunder Bay, Ontario, finally exposed the scheme to defraud Morrisseau. Not even the artist himself could have imagined the scale of the fraud, which in both the number of forged paintings and the profits made from their sale was likely the biggest art fraud in history—not in Canada or North America but anywhere in the world.Inside the biggest Art Fraud Norval Morrisseau was certain. “I did not paint the attached 23 acrylics on canvas,” he wrote in a typed letter in 2001 to his Toronto gallery representative, who had sent him color |

photocopies of works that had recently sold at an unrelated auction.

Morrisseau, then in his late 60s and suffering from Parkinson’s disease, was the most important artist in the modern history of Canada’s Indigenous peoples—the “Picasso of the North.” He had single-handedly invented the Woodlands school of art, which fused European and Indigenous traditions to create striking, vibrant images featuring thick black lines and colorful interiors of humans, animals and plants, as though they had been X-rayed and their insides were visible and filled with unusual patterns and shapes. He was one of the first Indigenous painters to garner national attention and the first to have a solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. “Few exhibits in Canadian art history have touched off a greater immediate stir,” swooned the Canadian edition of Time magazine after Morrisseau’s sold-out 1962 debut exhibition in Toronto. |

|

Artist and Shaman Between Two Worlds, Norval Morrisseau, 1980, shows the artist’s signature style: bold colors and a surreal sense of his subjects’ inner lives.

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; All artworks in this story used with the permission of the Estate of Norval Morrisseau, officialmorrisseau.com the discovery of Norval Morrisseau. I'd like to think...Jack Pollock is: The Art of Norval Morrisseau. Pollock figures prominently... By 2001, Morrisseau paintings routinely fetched thousands of dollars on the market. The works he now denied having painted were no exception. The auctioneer had advertised them as being from Morrisseau’s hand and claimed to a reporter writing about the dispute that, though he had obtained the paintings from an obscure seller, he had no reason to doubt their authenticity—he had already sold 800 of them without a single buyer’s complaint. Morrisseau, though justifiably incensed, wasn’t surprised that imitations of his work were being sold as authentic on the open market. As early as 1991, the Toronto Star reported the artist was complaining about being “ripped off” by fraudsters. But for years Canadian law enforcement did little to investigate the artist’s claims that forgers were imitating his work. Eventually, in the face of this inaction, Morrisseau’s lawyers advised him to notify galleries and auctioneers that they were selling fakes and warn them that they could be the subject of a court injunction, civil action or criminal complaint. Still the sales went on. It wasn’t until this past year, more than 15 years after the artist died from complications related to Parkinson’s, that an unlikely |

consortium of investigators, led by a homicide cop from the small city of Thunder Bay, Ontario, finally exposed the scheme to defraud Morrisseau. Not even the artist himself could have imagined the scale of the fraud, which in both the number of forged paintings and the profits made from their sale was likely the biggest art fraud in history—not in Canada or North America but anywhere in the world.

Morrisseau was born in the early 1930s. Consistent with Anishinaabe traditions, he was raised by his maternal grandparents on a reserve near Thunder Bay belonging to the Anishinaabe. Reserves were (and largely remain) small, poor, unproductive lands where the Canadian government had forced Indigenous people to live. Morrisseau’s grandmother was Catholic, and his grandfather, a shaman, taught him his people’s spiritual traditions. Fusing white and Indigenous cultures, rather than segregating them, would define Morrisseau’s life and art. When Morrisseau was 6, Canadian officials abducted him and sent him to a residential school. These infamous boarding schools were established by the federal government in the late 19th century. As at their counterparts in the United States, Indigenous students were stripped of their language, culture, community and family ties and were forcibly assimilated into the dominant white, Christian culture. In both countries students also frequently endured physical, sexual and emotional abuse, and Morrisseau later said that he’d endured sexual assault at school—among the experiences that caused lasting psychological and emotional damage, leaving him vulnerable to addictions to alcohol and drugs. |

|

Morrisseau, known as the “Picasso of the North,” at the Pollock Gallery in Toronto, 1975, beside a painting of mother and child—a frequent theme. The Globe and Mail / CP Images

By age 10, Morrisseau had returned to his grandparents’ reserve and become a budding artist, drawing and painting forbidden things. In Anishinaabe tradition, it was verboten to make visual art based on sacred oral traditions and myths. As he grew serious about his work, during his teens and early 20s, he attracted criticism in the community. “A lot of elders and [Anishinaabe] didn’t agree with what Norval was doing and what he was expressing in his paintings,” says Dallas Thompson, an Anishinaabe man who knew one of Morrisseau’s relatives. At the time, Canada prohibited Indigenous people from practicing their cultures (laws that were enforced until 1951). By putting spiritual material into his work, Morrisseau was defying both colonial and Indigenous pressures while |

fashioning a new artistic style that injected Anishinaabe ideas into Western art. His big, bold works were filled with swirls of bright paints portraying people and animals as receptacles for ancient spiritual myths. He viewed his art as a sort of therapy, and not necessarily for himself. “Why am I alive?” he once said. “To heal you guys who’re more screwed up than I am. How can I heal you? With color.”

Morrisseau became an instant celebrity in 1962, after a Toronto gallery owner named Jack Pollock (no relation to Jackson) discovered Morrisseau and began displaying his work, marking the first time an Indigenous painter’s work was shown in a contemporary Canadian gallery. The impact on the country’s art world was immediate and enormous. Every painting sold the first day. Eventually, Morrisseau became a practicing shaman and began signing his paintings with the name Copper Thunderbird, given to him as part of a healing ceremony. Before long, his art was included in shows in England, Norway, Germany and the U.S. |

|

In this 1978 diptych, The Storyteller: The Artist and His Grandfather, Morrisseau depicts his maternal grandfather, left, conveying ancestral stories to the artist, right. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

Morrisseau was known to friends and collaborators as soft-spoken but wry. Pollock called him “eccentric, mad, brilliant.” |

In a National Film Board of Canada short released in 1974, Morrisseau sits among his works wearing a purple shirt and a painted brown vest. He says that a great spirit promised to guide and look after him. “What more protection do I want?” Morrisseau says to the documentarian. “I don’t need to go to a big cathedral.”

|

French Land Acknowledgment

Reconnaissance des territoires traditionnels (Toronto)

Nous reconnaissons que la terre sur laquelle nous nous réunissons est le territoire traditionnel de nombreuses nations, notamment les Mississaugas du Crédit, les Anishnabeg, les Chippewa, les Haudenosaunee et les Wendats, et abrite maintenant de nombreux peuples diversifiés des Premières nations, des Inuits et des Métis. Nous reconnaissons également que Toronto est couvert par le Traité 13 avec les Mississaugas du Crédit.

https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/accessibility-human-rights/indigenous-affairs-office/land-acknowledgement/

Reconnaissance des territoires traditionnels (Toronto)

Nous reconnaissons que la terre sur laquelle nous nous réunissons est le territoire traditionnel de nombreuses nations, notamment les Mississaugas du Crédit, les Anishnabeg, les Chippewa, les Haudenosaunee et les Wendats, et abrite maintenant de nombreux peuples diversifiés des Premières nations, des Inuits et des Métis. Nous reconnaissons également que Toronto est couvert par le Traité 13 avec les Mississaugas du Crédit.

https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/accessibility-human-rights/indigenous-affairs-office/land-acknowledgement/